The Idea

I have been a Geocacher for a long time, and it has always been my wish to complete electronic caches alongside the classic ones. For years, there have been so-called Wherigo Caches. As you can tell from the website, these types of caches aren’t really maintained anymore. This is also evident in the technology used. They are scripts built internally using the programming language LUA in version 5.1.4.

Backstory

In the past, these caches were executed natively on Garmin GPS devices. I owned a Magellan GPS (Windows CE). Even back then, I had the desire to get it running on my GPS. Today, there is a native smartphone app from Groundspeak, but that lacks the challenge of familiarizing oneself with the technology.

WherUGo

It was technically possible to execute custom code on my Magellan GPS; you just had to copy the executable onto an SD card. I even received a GPS unit as a dev device from a Marketing Director at Magellan because mine didn’t have a compass. Unfortunately, I was inexperienced, and my project WherUGo was doomed to fail.

However, it was intended to lay the foundation for further ideas.

Flutter (with Dart FFI)

Since I want to play Wherigo caches on the desktop nowadays, I considered writing a Flutter app. The advantage would be that I could run it on desktop and potentially on smartphones as well. However, I didn’t want to use a Dart implementation of a newer LUA version, because the binary code wouldn’t be compatible. This left only the option of using the original LUA source code and utilizing it for the required platform.

This is possible because there is an intermediate layer for Dart to C code (FFI). However, this failed because I wasn’t familiar enough with the content of the LUA State Machine. So, I put the project on ice for later.

wxWherigo

Through my interest in microcontrollers, I came into increased contact with C and C++ again. Years ago (must be more than 12 years now), I had heard of a framework called wxWidgets. Aside from a few small steps, I didn’t have a real use case for it. It was great for building simple UI applications (which might run elsewhere too).

Since we are also in the age of “Vibe Coding,” I wanted to test the limits and dared to tackle the Wherigo project again.

Implementation

After having written a GWC (the file format for Wherigos) reader for WindowsCE and then again for Dart, it was now time to let the AI write a converter in C/CPP. I took the Dart implementation as input and fairly quickly received a functioning component that could export the metadata and every single object from a byte array.

I used CMake for my wxWherigo project, which is also available as Source Code.

LUA

Next on the agenda was the LUA Engine. I was able to build this very easily with CMake, but through the AI, I learned that there is a problem: the compiled LUA code is 32-bit (I was able to verify this with a hex editor). Since a new PC (I have a MacBook Pro with an M-processor) works with 64-bit and the engine can only correctly handle old code starting from version 5.4, the idea was to simply adapt the engine accordingly. It only affected one file, lundump.c, which I had to adjust to let 32-bit compilations run under 64-bit. The AI really helped me here, once I was able to convince it that the LUA Engine is fixed and doesn’t need to be updated every time.

wxWidgets

Now I needed a UI to display the data. The AI was consulted again because I wanted to build a Proof-of-Concept and not a product I could sell. What I had forgotten over the years is that wxWidgets is very limited in its UI scope; for example, it cannot replicate the macOS Glass UI. But that shouldn’t matter for my PoC. I just needed a functional UI and not an application that would win a design award.

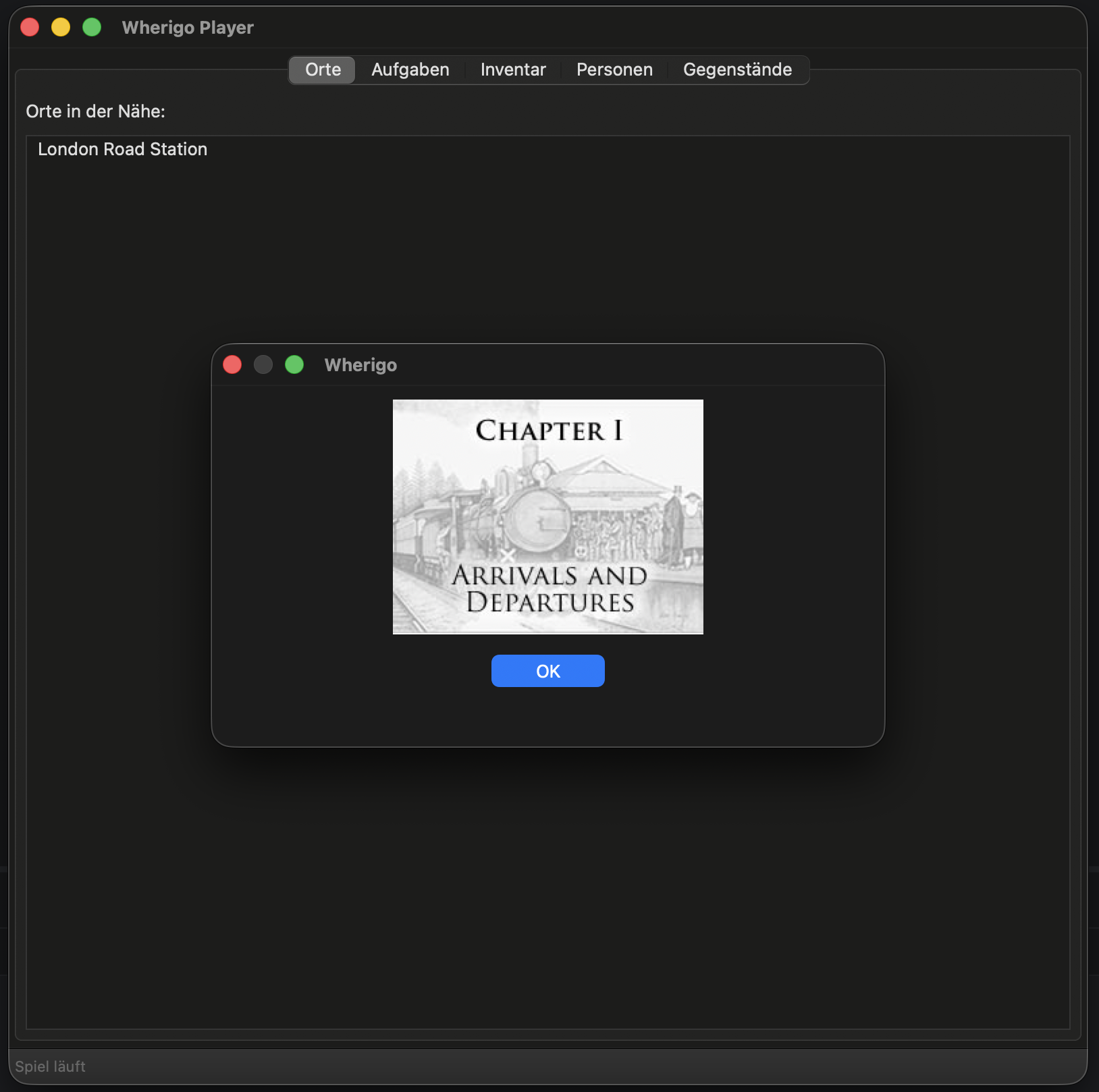

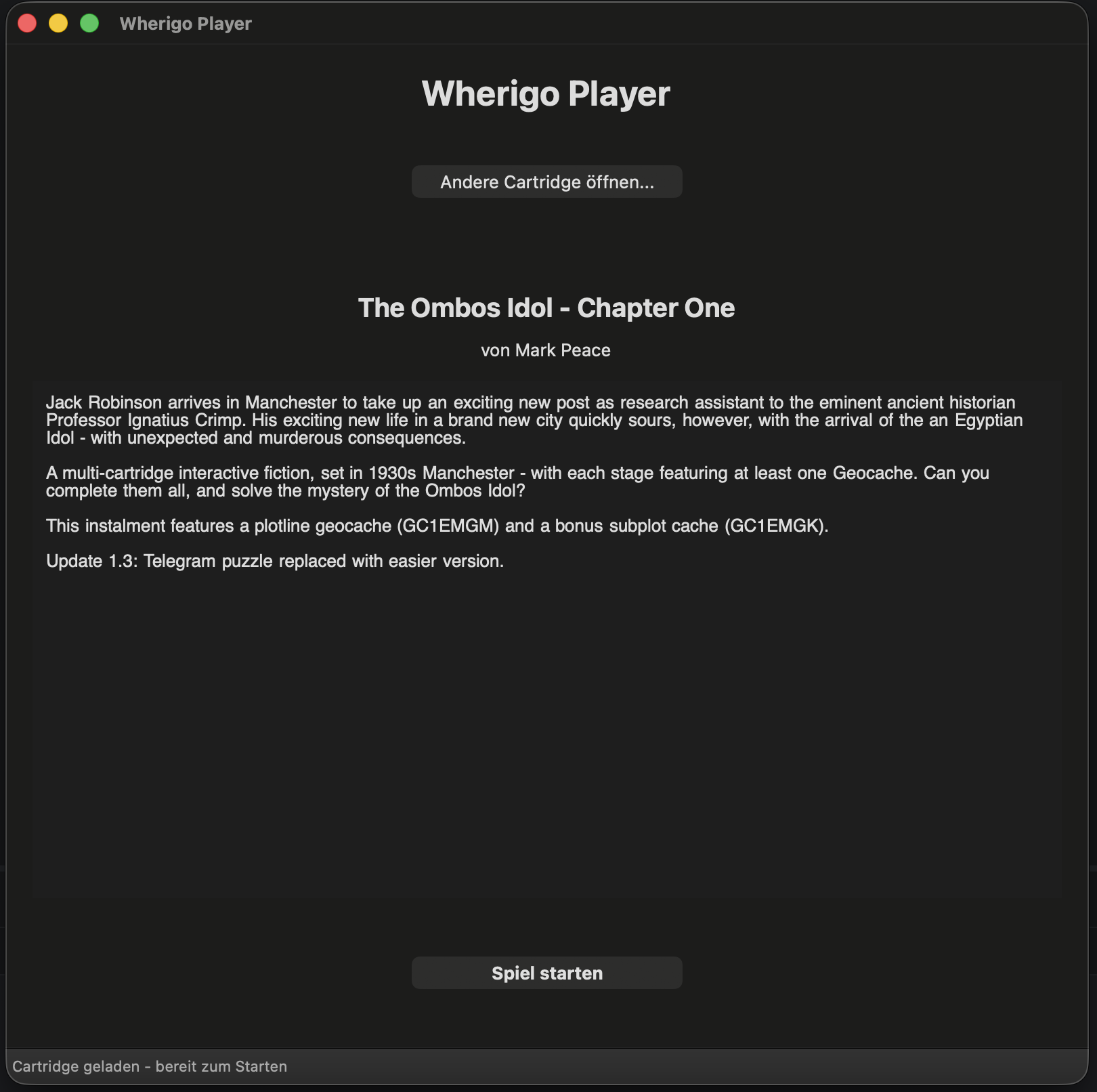

So, I downloaded 3 Wherigos to have real examples. The first attempt was to have a start screen built with a file selection dialog, which would then display the metadata of the caches.

As you can see in the screenshot, I was able to display the text and the splash screen image. Unfortunately, the texts are in a Windows character set, and I was unable to display German umlauts correctly. I checked in the official smartphone app and lo and behold, it was displayed incorrectly there as well. So, no further problem for me.

Gameplay

Now comes the most difficult part of the project (all done with Vibe Coding again). I let the AI throw the bytecode into the LUA engine. It aborted immediately because it didn’t know the object “Wherigo”. When I saw this message, I was totally happy because it proved two things: 1. the LUA engine can process 32-bit code, and 2. It actually understands what is supposed to happen there.

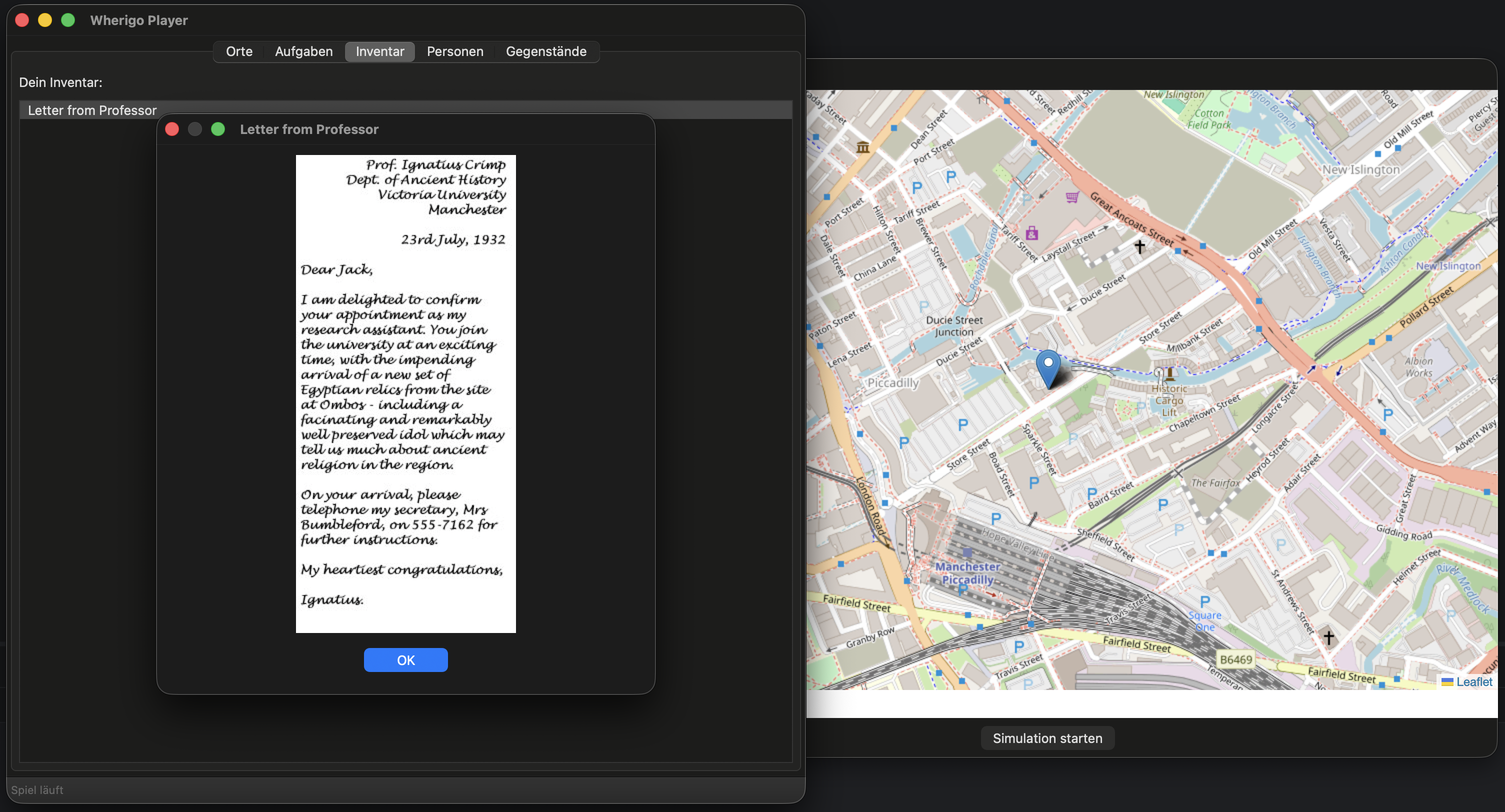

Through the AI’s training data, I was able to very quickly have a Wherigo object created, which also had the necessary functions as stubs. So, the AI had indeed heard of Wherigo internals before. I had the UI extended to show me more information (see screenshot above).

For one project, I let the OnEnter functions trigger on the zones, allowing me to trigger the events (in this case, multiple dialogs). Here too, the AI wrote the dialog source code for me so that I can display texts and images.

However, the UI wasn’t changed, so I didn’t see the next station. I asked the AI again and thus felt my way forward. In the end, I was able to read the final coordinates of the container in the dialog. — I know, if I had just dumped all the texts from the engine, I would have gotten them too, but the fun of the game would have been gone.

Now the only thing missing was getting the unlock code for the Wherigo. There seem to be two possibilities (one via metadata and one on the Player object). In the case of the first Wherigo, it was simply the code from the metadata. But there is a catch. The code is 16 digits long, but the website expects only 15 digits. You have to know that (wasn’t known to me before).

Further Functions

I still had two other caches that I couldn’t solve with this logic. So, by chance, I had picked good files. One had invisible zones, so I couldn’t click them directly via the UI. For this, I built a map that shows the zones via markers on the map. I still have to implement the triggering of these invisible zones. That will be exciting.

The third container works with timers. I don’t know why I’m not making progress there. I have to research further on this as well. But that’s exactly what makes the appeal of this project.

Other file formats like sounds are also missing. I will continue to pursue the project because many features are still missing.

Future

Should the project with wxWidgets ever near a complete implementation, I might consider building the whole thing as a multiplatform project in Flutter after all, because thanks to the extensive help from the AI, I then only have to transfer the C/C++ code to Dart. On the way there, I will definitely take you along.

comments powered by Disqus